Repo for the project: https://github.com/chaplin89/challenges

The ESET CrackMe Challenge 2015 is divided into two parts:

- This is the one you download from the ESET website. You are asked to reverse a UPX packed executable and find one password (Drevokokur). Then the application decrypts a message with this password that basically asks you to decrypt in the same way some unreferenced data inside the executable. Once decrypted, this unreferenced data gives you a link to download the 2nd part, which is the subject of this document. I won’t discuss the first part any further.

- The second part is made of an EXE and a DLL. The files to analyze are two: EsetCrackme2015.exe and EsetCrackme2015.dll

Introduction

This challenge aims to find three passwords. The application uses various obfuscation techniques, and I have set my goal to get things done with the minimum effort. Given the huge amount of obfuscation/hiding techniques used in this challenge, this paper is only meant as a guide to retrieve the three passwords. I won’t describe many things in detail if you want to deepen some topics, you can check the repo linked at the beginning of the post.

Its structure is as follows:

| Analysis | Is divided into subfolders. Every subfolder’s name is the ID of a resource (see below). Subfolders contain files related to my analysis, IDA DBs, tools I wrote, and, eventually, the resource itself decrypted (if the original is encrypted). |

| Resources | Contains raw resources dumped from the challenge. |

| Utility | Contains utility I wrote to analyze the .net stuff |

| Resources.xlsx | An overall description of all the resources. |

| EsetCrackMe2015.exe EsetCrackMe2015.dll | The challenge itself. |

For this challenge, I used:

- IDA Pro as disassembler/frontend of WinDBG for debugging native code (either for the user mode and the kernel-mode part)

- DIE (Detect it easy) to analyze the files

- dotPeek to reverse the .net stuff

- de4dot mainly to rename obfuscated symbols

- Other tools I wrote from time to time

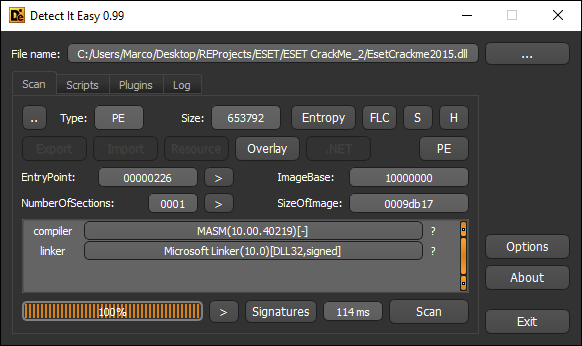

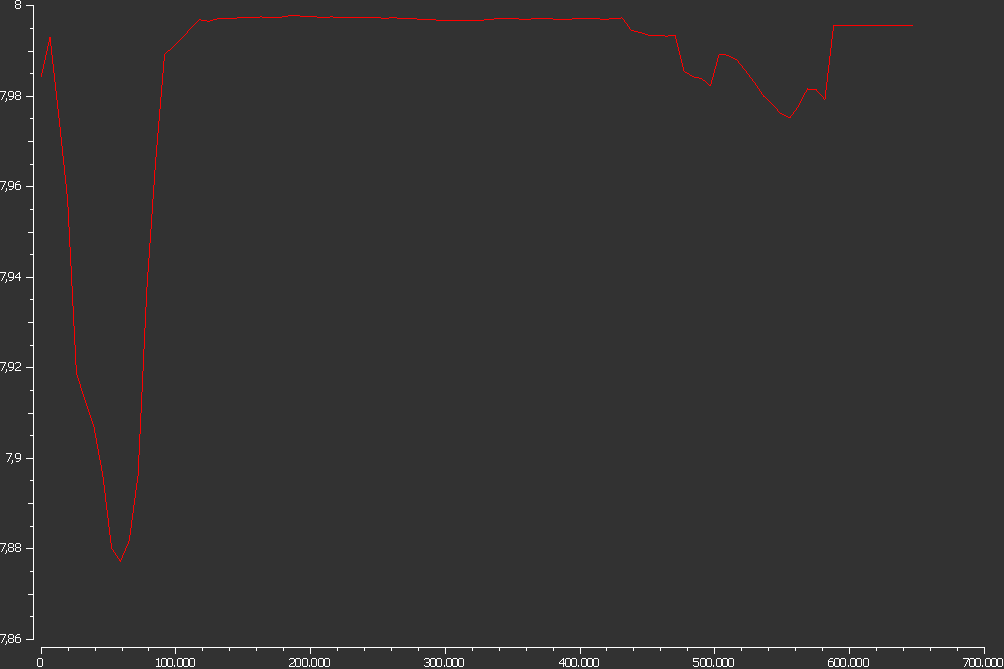

Library

DIE Analisys

Entropy

Rationale

The DLL is just a collection of resources with a very simple schema:

- 2 Byte: ID

- 4 Byte: Size

- N Byte: data Some of them are encoded/encrypted, others are not. The encryption/encoding schema varies, see Resources.xlsl.

I’ll often reference these resources.

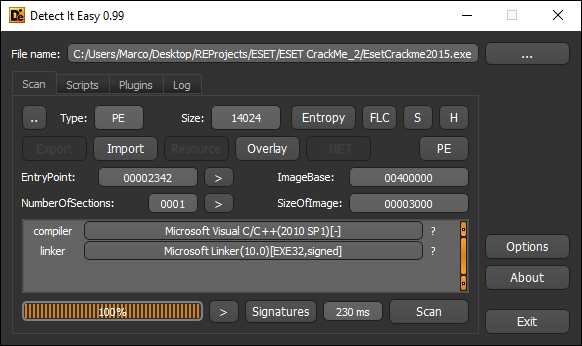

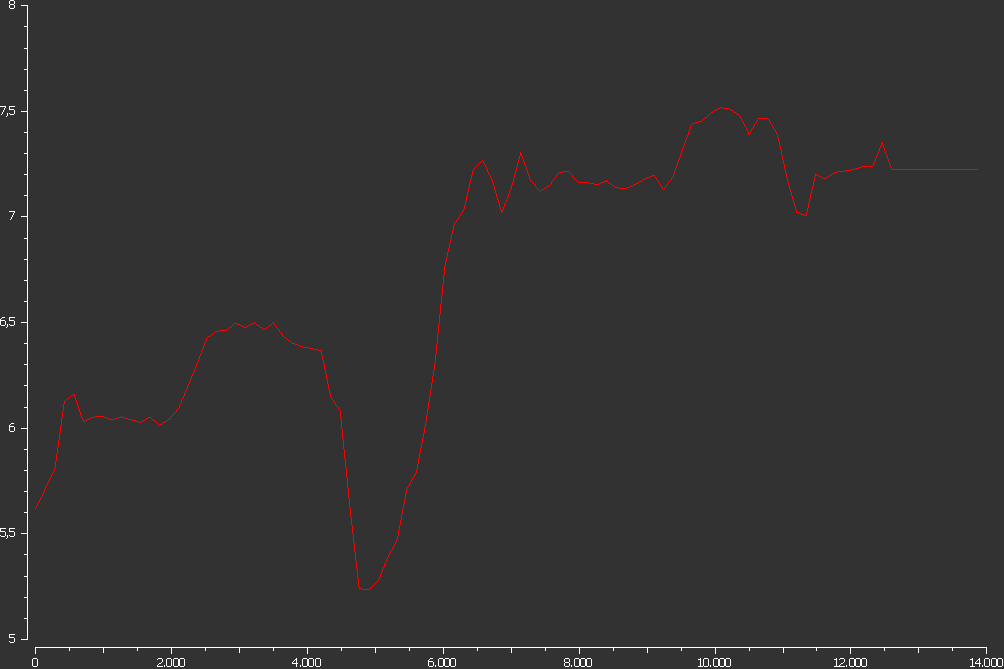

Executable

DIE Analysis

Entropy

Note: the file is small and a large portion of it is made of digital signature (high entropy) so the DIE analysis is distorted.

Note: the file is small and a large portion of it is made of digital signature (high entropy) so the DIE analysis is distorted.

Rationale

The application decrypts resource with ID 0x0101 using the key “Irren%20ist%20menschlich” (resource ID 0x0003), then enters in a loop.

In this loop, it repeatedly calls the decrypted resource until its result is not zero. At that time, it waits for some events to occur (see below), then it starts from the beginning.

The application also starts a thread that makes it communicate with every entity that requests something through the PIPE \\.\pipe\EsetCrackmePipe (ID 0x0002) with a simple protocol:

- Request

- 1 byte: Type of request

- 2 bytes: ID

- Response

- 1 byte: Type of request

- 2 bytes: ID

- 4 bytes: size (if the request is of type 1)

- N byte: data (if the request is of type 1) Type 1 is used to retrieve resources; type 2 is used to signal events.

First password

In the decrypted routine that is called by the application, a lot of things can happen.

The first time the resources with ID 0x0102, 0x0103, 0x0104 are loaded:

- The first is a (simple) virtual machine.

- The second is the bytecode of a program that uses process hollowing to inject the resource

0x0151in Svchost.exe. - The third is the bytecode of a program that can take the resource data, a path in input, and dump the resource in the path. I leave out the VM analysis for the moment because it is not important for the first password. All we need to know for now is that this program injects something in svchost.exe

The context can easily see this because if you break at 0x00060AEC (the VM main loop), you’ll see that at some time, the process svchost.exe is created suspended, so it’s easy to guess what’s going on. Also, if you look for the processes linked with the GUI that stands out when you open EsetCrackme2015.exe, you’ll see that it is svchost.exe and not EsetCrackme2015.exe

We can see what is injected by dumping the resource on disk after decryption (Resources/0x0151_Injected/Injected.exe). It doesn’t use any debugging protection, so you can attach your debugger to the right instance of svchost.exe and dump process data.

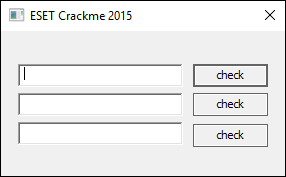

Analyzing the injected program, we can see that it is a straightforward dialog-based application:

It computes a hash on the inserted password and then compares them against a pre-loaded hash on the button click events. These hashes are loaded from the main application through the PIPE, then decrypted (ID 0xBB01). The algorithm which is used to compute hash is SHA-1, so I consider this a dead end.

The application also starts a thread that replaces the DlgProc at runtime via SetWindowLong.

The new DlgProc is almost useless. Still, it intercepts the OnClick event, and it leads us to the first password because it encodes the first inserted password with a slightly modified BASE64 and compares the result to a pre-loaded string (for other details, see 0x00072360). This string is the resource 0xBB02.

Applying the algorithm conversely on the loaded string, we can see the first password: Devin Castle, a nice place in Slovakia:

Second Password

Inserting the first password lets us move to the second stage of the challenge: the driver.

When a password is inserted correctly, an event is signaled through the PIPE. The thread that manages the PIPE in the main application records the event and wakes up the main thread. The main thread re-runs the decrypted DLL’s routine. Basing on the event signaled, it can start the VM program 0x104 to write some resources somewhere. In the case of the 1st password, this resource is the one with ID 0x0152, and the place is the application working directory.

This resource is a zip folder that contains a Win32 legacy driver that you have to install.

This driver is a ramdisk, its architecture is more or less the same that you’ll find an example on the Microsoft website (see: Analysis/0x0152_Drv.zip/RAMDISK). You can read that code to understand the main functionality of this driver.

There are, of course, some important differences that I’ll explain.

The routine that changes most is the DispatchReadWrite: basically, the principle is that you write something in the ramdisk, then when you read it, the driver decrypt what you wrote on the fly. One of the differences between this driver and the MS example is that this driver does not create any symbolic link, so every read/write is done by creating a handle to the device name that is \\?\GLOBALROOT\Device\45736574\.

The driver in the “add” routine starts many threads that use the PIPE to communicate with the application. The application gives the driver the string “ESETConst” (ID 0xAA02) that is used as the name of a registry key and a program for the virtual machine that lies inside the driver (ID 0xAA06).

This program is the one that decrypts what you write inside the ramdisk.

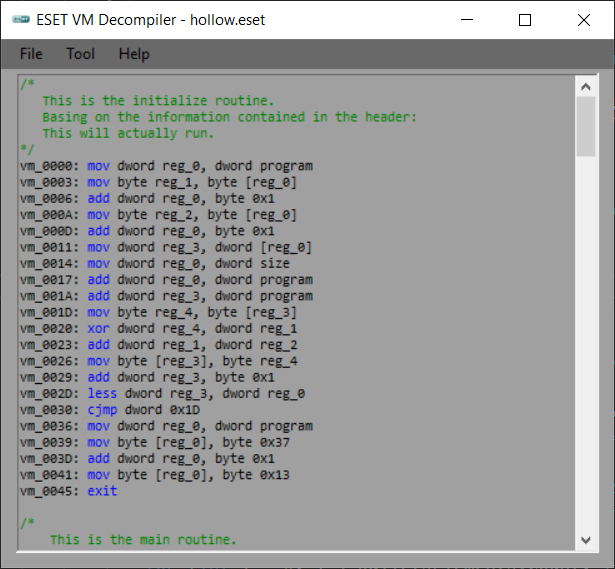

Here we are forced to analyze this VM. I wrote a VM bytecode decompiler in an assembly-like language. You can find it inside Analysis/0x0102_VirtualMachine/VMDecompiler (it has some minor bug but should always produce valid disassembly):

The VM that runs inside the driver is slightly different from the one that runs inside the application. In particular, the offset of the header fields is different.

The header contains the following fields:

- 2 Byte: Signature

- 4 Byte: Size

- 4 Byte: MainOffset

- 4 Byte: library flag The signature is compared against a constant (“1337” for app VM, “3713” for driver VM). If the signature does not match, the execution begins from the 1st byte following the header (decryption stub); if it matches, the execution begins from the MainOffset byte following the header.

VM is quite simple. It can support 255 opcodes, but only 15 of them are implemented. If the program contains not supported opcodes, the program terminates.

The VM virtualize a stack, 4 MB, and a CPU with 16 registers:

- Register from 0 to 5 are GP

- 6 is SP

- 7 is the beginning of the loaded program

- 8 is loaded program size

- 9 is the library flag

-

Register from 10 to X, where

10<X<16is a constant passed to the VM, contains some DWORD passed to the VM (input data) Here is a brief description of opcodes, for further reference, see the file Analysis/0x0102_VirtualMachine/VMOpcodes.xlsx: - Terminate the program.

- Move data. The destination is a register.

- (Native) Call. Make a call to the argument.

- Call the library. Arguments are the hash of the name of a (loaded) library and the hash of the name of a function exported by the library.

- Push argument in the stack (load argument in memory pointed by SP and then decrement SP).

- Pop dword from the stack into a register (copy dword from memory pointed by SP into register then increment SP).

- Logical operations, the first operand is a register. The operation could be: not equal, equal, minor. If the condition is met, a flag is set.

- Jump. This can be conditional. In that case, the IP is updated if the flag is set. (Virtual) Call. Push IP, then change it with argument.

- Pop dword from the stack into IP.

- Arithmetic operations, the first operand is a register. The operation could be: add, sub, left shit, right shift, ROR, ROL, module.

- Allocate memory. The operand is the size. The pointer to allocated memory is saved in Register 0.

- Deallocate memory. The operand is the pointer. The program pointed by the argument is loaded in memory takes the place of the loaded one.

- Terminate the program. This is called when an invalid opcode is found.

The VM iterates through every byte in the program and calls the appropriate handler until it finds an exit opcode or an invalid one. The handlers accept a structure (Context) in input that contains the status of the CPU.

The programs that run inside the driver could be seen in Analysis/0x0152_Drv.zip/VM Programs. In this program, the odd thing is that the registry key (ESETConst) is checked against null but seeing the dispatch RW routine, it is easy to spot that the VM can’t start if the key is null.

In fact, reversing the algorithm, we find the 2nd password: Barbakan Krakowski a building in Krakow:

I wrote a program to emulate the behaviors of the VM in a high-level language. In Analysis/0x0152_Drv.zip/DriverVMEmulator, there is a software that decrypts the resource 0x0155 as the driver would do. It can also run the algorithm conversely to find what the registry key should be: Reversing is great.

The result of the decryption is this bitmap:

Third password

Guessing the 2nd password lets us move to the third part of the challenge.

When you guess the 2nd password, the application writes the resource with ID 0x0153, 0x0154 in its working folder. These are two .net applications called PunchCardReader.exe and PuncherMachine.exe.

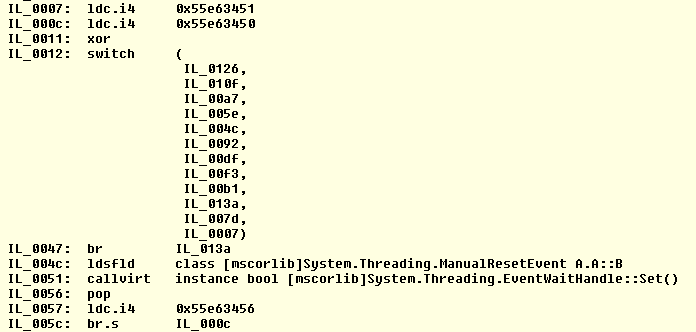

Both of them are windows form applications. Both are obfuscated with a custom obfuscator (I guess). The obfuscation schema is the same, and it is straightforward:

Most of the obfuscation is based on splitting function bodies into different cases inside a switch (num1^num2). One of the integers does not change among different loops, but the other can be reassigned inside the various cases. In this way, the next time the loop is executed, it can enter in another case. Every case usually ends with a branch to the switch address:

Strings are not directly visible. They are merged together and constitute a blob of data. There are some stub methods, one for each string, that know how to extract strings from this blob of data. As various obfuscation schemas do, invalid C# names are used. In IL, you can, for example, re-use the same name for different types because, in IL, you always have to fully-qualify everything you use, so there is no ambiguity. My first attempt to understand what the software does was to write a plugin for de4dot. I wrote the skeleton of the obfuscator, but then I realized that important functions are very small and it is not hard to understand what they do, so I’ve chosen a different approach:

First of all a “de4dot –un-name !.*” is by default. So I’ve used dotPeek to decompile the program and recreate the VS project. With very few changes (mainly moving variable declaration) and some textual parsing (see Utility/PunchStringDeob), I was able to compile both projects.

In these applications, resources loaded from the main app are decrypted with the AES algorithm in ECB mode (which I think could explain a lack of entropy at the end of DLL). The key is an MD5 hash computed against the body of some methods that has a particular attribute and the attribute itself. Of course, when I recreated the project in VS, the MD5 hash has changed, so I wrote a program that emulates the hash computation using the original file as input, then I hardcoded the key in the recompiled programs to make things work (see Utility/ExtractKey).

Meet PuncherMachine.exe

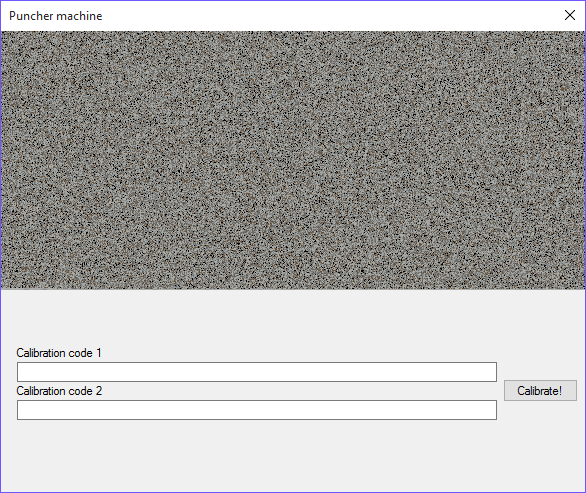

Once open, it shows this image:

It uses PIPE to check if EsetCrackme2015.exe is open. If it isn’t, it won’t start.

Of course, here I made an “ignorant” attempt to make the application load the file extracted from the driver. Of course, it didn’t work.

There are some odd things inside PuncherMachine.exe that promptly stand out.

It tries to refer to a resource named “resource0” and there is no such resource in the assembly. It tries to retrieve a resource from the main application with ID 0xFF03, and there is no such resource in the DLL. You can make the application find resource0 into the assembly, or you can perform a “man in the middle” attack through the PIPE to inject the resource; the result is pretty much the same: a hash is computed on this resource and is checked against the hash of the file that you choose from the file dialog. If it matches, the software leads you to the 2nd stage; if it doesn’t match, an “Invalid punchcard!” message is shown.

If the application doesn’t find one or the other, it checks the hash of the input file against an unknown hash (resource ID 0xFF02): 95eceaa118dd081119e26be1c44da2cb. Then the check fails because I don’t have the file that has that MD5 hash, but maybe I’m missing something here. In fact, I’m quite sure that there is far more than it seems in the bitmap. Of course, a bitmap full of noise seems very strange in a challenge that is stuffed with mysteries. My guess is that there is another bitmap that can be decoded starting from the first, and that bitmap has the required hash. By the way, I haven’t spent time on this because the bitmap plays a minor role in this process, and it is not functional to retrieve the 3rd password. Also, as I’ll explain later, this bitmap, although I think it is decoded well, does not allow me to complete the challenge.

At this point, I made the recompiled software load “resource0”, which is my bitmap.

Selecting a valid bitmap makes the GUI change:

I’m asked to insert two strings: calibration code one and calibration code 2.

Seeing the handler to the “Calibrate!” button click, I can see that “Calibration code 1” is given in input to a method of an assembly.

The assembly is obtained through PIPE (resource ID 0xFF04), and the method is called “createMethod”.

After dumping the assembly on the disk, I could analyze it (see Analysis/0xFF04_CalibrationDynMethod.dll/CalibrationDynMethod for full code). The assembly is very simple and, luckily, is not obfuscated. It can create the skeleton of a method with Reflection.Emit classes. In this skeleton, some instructions are missing. The method uses the input constants as hashes to decide which opcode to emit, so understanding what the generated function should do is the first step to decide which opcode should be there. It is not that hard because it contains some hardcoded constants, and searching these constants on Google, it comes out that this is the “Knuth Hash” algorithm and the missing instructions are then: ldarg.0 and mul.

Basing on this, the Calibration code 1 should be 0364ABE72D29C96C (see Analysis/0xFF04_CalibrationDynMethod.dll/CalibrationDynMethod_HashTable.txt).

The created method is then called inside a loop. Every char of the calibration code two is added to a char in a list, and then the Knuth Hash is computed based on this input. Every hash in output, then, should be the key of a hashtable for the “calibration process” to be successful. This hashtable is the resource 0xFF00.

It comes out that the only string that met this condition is “Infant Jesus of Prague” (that it is also the third password), a statue in Prague:

4th Condition

Honestly, at this point, my interest in the challenge really dropped down. It was fun to learn IL and C# a little bit to found the 2nd password, and I was expecting some kind of escalation, but the third one is actually way too boring and way too easy compared to the 2nd. So my expectations were disillusioned.

The truth is that it was hard to stay in the right mood in order to continue the challenge, and I continued until I could do things that required limited effort, but I gave up at the real end because I thought it wasn’t fun anymore.

By the way, if you want, I have paved the way, and you have all you need in order to finish the challenge; maybe you can prove I was wrong.

Ok, enough blah-blah, back to the challenge.

If you look inside 0x10000CDD, you’ll see that there are four conditions to meet in order to make the application show you a greeting message. Three of them are events fired when you enter the right passwords. A 4th condition is an event fired by PunchCardReader.exe; we’ll get there.

What matter for the moment is that when you enter the valid calibration codes, the GUI changes:

As you can see on the “PunchIt!” button handler, it can encode the string that you insert in the bitmap that is then written on disk with the name punch_card_XXX.bmp (where XXX is in the range 000-999) with a fancy animation and a very relaxing background noise.

The next step is to figure out what should be encoded in bitmaps.

Meet PunchCardReader.exe

Once opened, it shows this dialog:

This is another windows form application. It just has one button in the interface: “Read punch card”.

The principle, of course, is to produce some “punch cards” from PuncherMachine.exe then read these “punch cards” from PunchCardReader.exe.

In the disassembled program, it could be easily seen that punch cards are decoded into a string. These strings are passed to the method of an assembly.

The assembly is the resource 0xFF05, and it is very similar to the former. It now accepts a string array that is used as IL instructions inside the skeleton of the method. So inside these bitmaps, created by PuncherMachine.exe, there should be encoded a list of IL instructions.

Seeing the assembly, it could easily be spotted what these instructions should be. The code does pretty much this:

((x(0xDEAD,0xBEEF) ^ y(0xCAFE, 0xBABE)) ^ 0xFACE) ^ -229612108 == ToUInt32(“ESET”)

You have to spot what functions x and y are. There is another unknown instruction at the end, but it is clear from the signature of the returned method that it is a ret.

So it is very easy to spot the instructions:

- x = mul

- y = add

- z = ret

Punching the bitmap with mul, add and ret does not let PunchCardReader.exe validate the bitmaps, although these seem to be the right strings. I spent very little time on this, but I think that it is due to the fact that the original bitmap is wrong, and this does not let the decoding process work well.

If this assumption is correct, I think that two hypotheses are the most plausible:

- The re-implementation in C# of the VM program that runs inside the driver is bugged. At first glance, this seems unlikely to me because it produces an overall valid bitmap, but who knows.

- There is another bitmap that can be extracted from the 1st in some way (like trying to decrypt the content of the bitmap, XOR it, or whatever). That bitmap is the one that has the unknown hash and will allow the decoding process to work well.

Conclusion

That’s all! After all, it is a nice crackme. I think the VM part is the best because it is very well written and stable. Kudos to the authors.

I am looking forward to the 2016 challenge bye.